Sports in Europe; Kansai Gaidai, College of Global studies, May 2020 (Online course)

Showing posts with label Politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Politics. Show all posts

Friday, July 3, 2020

Monday, March 23, 2020

Japan Focus. Special Issue: Japan’s Olympic Summer Games - Past and Present, Part II

(Japan Focus is an excellent open access journal)

Introduction for Part II by Jeff Kingston

Olympic Moment

1 - William Kelly - Bringing the Circus to Town: An Anatomy of the Olympic Movement

2 - Stephen Wade - Did the 2016 Olympics change Rio de Janeiro? Not Much - At Least Not for the Good

Fool’s Gold

3 - David McNeill - Spinning the Rings: The Media and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

4 - Michael A. Leeds - Can Cities Bring Home the Gold?: What Economic Theory Tells Us about Hosting the Olympic Games

5 - Eva Marikova Leeds - Tokyo 2020: Public Cost and Private Benefit

Paralympics

6 - Anoma P. van der Veere - The Tokyo Paralympic Superhero: Manga and Narratives of Disability in Japan

7 - Susan S. Lee - Promises of Accessibility for the Tokyo 2020 Games

Looking Back

8 - Mark Schreiber - 1940 Tokyo: The Olympiad that Never Was

9 - Christian Tagsold - Symbolic Transformation: The 1964 Tokyo Games Reconsidered

Dissenting Opinions

10 - Taro Nettleton - Light, Currency, Spectacle, and War: Kobayashi Erika’s She Waited (2019)

11 - Koide Hideaki, translated by Norma Field - The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and the Tokyo Olympics

12 - Shaun Burnie - Radiation Disinformation and Human Rights Violations at the Heart of Fukushima and the Olympic Games

13 - Akihiro Ogawa - As If Nothing Had Occurred: Anti-Tokyo Olympics Protests and Concern Over Radiation Exposure

14 - Sonja Ganseforth - Anti-Olympic rallying points, public alienation, and transnational alliances

15 - William Andrews - Playful Protests and Contested Urban Space: the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Protest Movement

16 - Alexis Dudden - An Opportunity for Japan to Change People’s Perception

17 - Sean Michael Wilson, illustrated by Makiko Kodama - ‘Tokyo and Olympics Guide’

Friday, March 20, 2020

Article of the day: Coronavirus: For the sake of athletes, it's too soon to cancel the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

Coronavirus: For the sake of athletes, it's too soon to cancel the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

For many people, the COVID-19 pandemic became real when professional sports leagues around the world suspended their seasons. Amateur competitions followed suit, with many international sports federations cancelling their championships. But what about the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games?

The International Olympic Committee continues to support Tokyo 2020’s preparation and encourage athletes to train for the Games scheduled to be held July 24 to Aug. 9.

The IOC’s approach should not come as a surprise. Since the start of the modern Olympics in 1896, only the 1916, 1940 and 1944 Games have been cancelled — and that was because of the First and Second World Wars. The 1920 Olympic Games went ahead after the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, a deadly strain of influenza that infected close to 500 million people globally and claimed the lives of approximately 50 million people.

Now, 100 years later, the IOC and Tokyo 2020 are faced with an eerily similar pandemic, raising questions about whether the Games should be cancelled for the fourth time in history.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been concerns raised about the perceived health risks of holding the Olympics. As Japan experienced rising numbers of cases in February, IOC member Dick Pound suggested organizers had until May to make a final decision.

Decision rests with IOC

Amid these fears, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Aby stated: “We will overcome the spread of the infection and host the Olympics without problem, as planned.” IOC president Thomas Bach has made similar statements; ultimately, the decision lies with the IOC.The financial costs of hosting such a massive global event also weigh heavily on any decisions. The official budget for hosting the Tokyo Games is $US12.6 billion, with $7 billion to be covered by the Government of Japan and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and $5.9 billion from IOC contributions, sponsorship, licensing and ticket sales. However, a 2019 report from the Board of Audit of Japan shows the actual costs are closer to $26 billion.

There would be a substantial revenue hit for organizers if the Games went ahead without spectators. A loss of ticket sales alone would decrease the projected revenue by 13.5 per cent. Broadcasters are also concerned that television viewers would find empty stands off-putting. This will be a significant point for the IOC to consider because broadcasters contribute billions to the IOC coffers — NBC paid $4.38 billion to have the U.S. broadcast rights for all of the Olympic Games from 2012 to 2020.

Then there’s the additional positive bump to the local economy that all Olympic host cities experience during the Games.

One thing for certain is that the cost of cancelling increases the longer organizers wait to make a decision.

The athletes’ perspective

The perspective of athletes is often lost amid all these billion-dollar debates about the cost of cancelling the Games.The months leading up to an Olympics is the time many athletes need to qualify for the Games. The IOC and the athlete’s National Olympic Committee set specific criteria that must be achieved — for example, the Olympic qualifying time for swimmers in the 100 metres is 48.57 seconds for men and 54.38 seconds for women. Additionally, some athletes must then compete and qualify at their country’s Olympic trials.

Great performances are the culmination of a perfectly timed program, designed to allow athletes to qualify while staving off peak performance results for the Olympic Games. It is an intricate science of balancing volume and intensity of training, while sharpening one’s mental skills.

It’s not unusual for an elite athlete to travel to several different countries across the globe in a span of one month to achieve a qualifying result. But national sport organizations like Athletics Canada are now instructing their athletes travelling and training abroad to return home.

With competitions being cancelled and countries rapidly closing their borders to international travel, the opportunity to qualify for the Olympic Games increasingly narrows.

Limited opportunities

That means even if the Olympics go ahead, athletes who have not yet met the Olympic qualifying standard may have a limited opportunity to qualify to represent their country, if at all.Read more: The secret formula for becoming an elite athlete

However, even for the athletes who have already qualified, the uncertainty of the Olympic Games is still stressful. Regardless of the IOC’s decision, some athletes may weigh the risk and rewards and choose to not participate in Tokyo 2020.

In 2016, the threat of the Zika virus resulted in many top athletes electing to sit out the Rio Olympic Games. At the 2010 Commonwealth Games held in Delhi, India, Canadian swimmer and former world-record holder Annamay Pierse contracted dengue fever and never recovered, ending her athletic career. And during the Spanish flu, professional baseball games continued as normal, resulting in many players contracting the virus.

Rewards may outweigh the risks

Despite this, many athletes may deem the rewards outweigh the risks. Athletes are well aware of the controversial Goldman’s dilemma, a research study that found 52 per cent of elite athletes surveyed said they would take a drug that would guarantee an Olympic gold medal even if it meant they would die five years later. While some researchers have challenged these results over the years, Goldman’s results highlight the value of the Olympic Games to world-class athletes.The Summer Olympic Games occur once every four years, and for the athletes, it is a culmination of perhaps a decade of training and preparation for a single moment. So it is reasonable to assume there are many athletes willing to take the risk to become an Olympian and have a chance at winning a gold medal.

While the Olympic Games are significant to the athletes, they are equally important to the world. The Olympic Charter states:

The goal of Olympism is to place sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity.If COVID-19 recedes in the coming months, the Olympic Games may be able to deliver some sense of healing — uniting nations in celebration. If the disease continues to grow exponentially, its trajectory will force the IOC to cancel or suspend the Games.

Ultimately, when it comes to COVID-19, we don’t know what we don’t know, and perhaps the IOC’s delay for a final decision may just be prudent at this time.

Nicole W. Forrester, Assistant Professor, School of Media, Ryerson University and Lianne Foti, Assistant Professor , University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labels:

Article,

coronavirus,

Modern Olympics,

Politics,

Tokyo Olympics

Friday, February 14, 2020

Japan Focus Special Issue: Japan’s Olympic Summer Games - Past and Present

Here is the TOC of the open access journal Japan Focus' special issue on Japan’s Olympic Summer Games:

Introduction

Branding and Identity

1 - Jeff Kingston - Diversity Olympics Dogged by Controversy

2 - David Leheny - Opening a Storyline in the 2020 Olympics

3 - Gracia Liu-Farrer - Japan and Immigration: Looking Beyond the Tokyo

4 - Tessa Morris-Suzuki - Indigenous Rights and the ‘Harmony Olympics’

5 - Claire Maree - “LGBT issues” and the 2020 Games

6 - Ian Lynam - The Small Olympics

Past as Prologue

7 - Gerald Curtis - Celebrating the “New” Japan

8 - Akiko Hashimoto - The Tokyo Olympic Stadium: Site of National Memory

9 - Asato Ikeda - The Tokyo Olympics: 1940/2020

10 - Robert Whiting - The 1964 Olympics

11 - Kazuhiko Togo - Unease about Tokyo 2020

12 - Roy Tomizawa - 1964: The Greatest Year in the History of Japan -- Three Reasons Why

13 - Helen Macnaughtan - From the Witches of the Orient to the Blossoming Sevens: Volleyball and Rugby at the Tokyo Olympics

Environment

14 - Robin Kietlinski- Trash Islands: The Olympic Games and Tokyo’s Changing Environment

15 - Peter Matanle- Confronting the Olympic Paradox: Modernity and Environment at a Crossroads in Downtown Tokyo

Introduction

Branding and Identity

1 - Jeff Kingston - Diversity Olympics Dogged by Controversy

2 - David Leheny - Opening a Storyline in the 2020 Olympics

3 - Gracia Liu-Farrer - Japan and Immigration: Looking Beyond the Tokyo

4 - Tessa Morris-Suzuki - Indigenous Rights and the ‘Harmony Olympics’

5 - Claire Maree - “LGBT issues” and the 2020 Games

6 - Ian Lynam - The Small Olympics

Past as Prologue

7 - Gerald Curtis - Celebrating the “New” Japan

8 - Akiko Hashimoto - The Tokyo Olympic Stadium: Site of National Memory

9 - Asato Ikeda - The Tokyo Olympics: 1940/2020

10 - Robert Whiting - The 1964 Olympics

11 - Kazuhiko Togo - Unease about Tokyo 2020

12 - Roy Tomizawa - 1964: The Greatest Year in the History of Japan -- Three Reasons Why

13 - Helen Macnaughtan - From the Witches of the Orient to the Blossoming Sevens: Volleyball and Rugby at the Tokyo Olympics

Environment

14 - Robin Kietlinski- Trash Islands: The Olympic Games and Tokyo’s Changing Environment

15 - Peter Matanle- Confronting the Olympic Paradox: Modernity and Environment at a Crossroads in Downtown Tokyo

Labels:

discrimination,

environment,

identity,

immigration,

LGBT,

memory,

Modern Olympics,

Politics,

Tokyo Olympics,

women

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Article of the day: Caster Semenya v IAAF: ruling will have big implications for women's participation in sport

Caster Semenya v IAAF: ruling will have big implications for women's participation in sport

When can a woman not compete with other women? This is, in essence, the question at the heart of the hearing currently before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), the international body that helps settle disputes related to sport. The ruling in the case of Mokgadi Caster Semenya and Athletics South Africa v International Associations of Athletics Federations (IAAF) is due at the end of April.

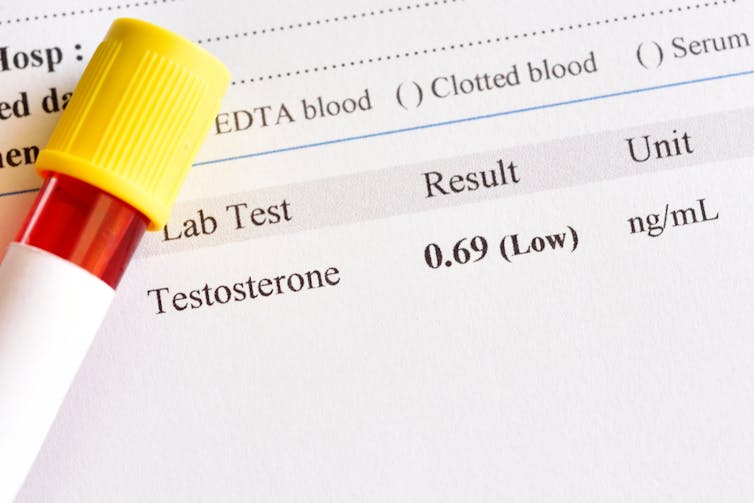

The case centres on the legality of a 2018 IAAF eligibility regulation for women with differences of sex development (intersex women), defined by the IAAF as women who have testosterone levels of over five nanomoles per litre of blood (nmol/l) and whose bodies can ostensibly use that testosterone better than other women can. Under these rules, women athletes with differences of sex development would have to reduce, and maintain, their testosterone levels to 5nmol/l or less in order to compete. The reasoning behind the regulation is that women with naturally high testosterone levels, and whose bodies are apparently highly sensitive to that testosterone, have a significant performance advantage over their peers in certain events.

However, this assertion has to be called into question. First, because research has been unable to prove a direct, causal relationship between testosterone levels and athletic performance – given that so many other factors play a role. And second, because there is no valid laboratory test to determine a woman’s degree of sensitivity to testosterone. Currently, the IAAF mandates physical, gynaecological, and radiological imaging to determine physical signs (such as an enlarged clitoris) as a proxy for testosterone sensitivity. However, this approach is not reliable, liable to false interpretation and subjectivity, and widely viewed as inappropriate and an invasion of privacy.

The case so far

In 2015, following another case before the CAS, a previous iteration of the regulation was suspended and the IAAF was given a deadline to produce new evidence to uphold regulating women’s participation in this way. The IAAF subsequently developed the now contested 2018 regulation on the basis of a new study, which showed a supposed “performance advantage” for specific track events.However, as my co-author and I argued in a BMJ editorial, this study was shown to be flawed and the authors subsequently acknowledged errors in the data used for the research. This is a red flag of the “science” that underpins the 2018 IAAF regulations. It draws into question the justification for the regulation for these, and indeed any, athletic event. It is against this background that we arrive at the 2019 CAS hearing.

Testosterone levels

Sports organisations have been grappling with the question of eligibility for years now. In reality, however, the science of this issue is quite clear. From a scientific and medical standpoint, we know that testosterone is not the only – or even primary – indicator of sports performance. Indeed, there are many other factors at play – including training, funding, and access to resources – in the development of a winning athlete.Further, in non-athletes, testosterone ranges between 0.4-2.0nmol/l in girls and women. In elite women athletes, the testosterone range has been shown to be between 0.4-7.7nmol/l, and that women can and do have much higher levels than that, which can also overlap with men’s ranges. So an arbitrary 5nmol/l limit for women could have the effect of capturing and regulating a much larger group of female athletes than intended, including women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (who naturally have high levels of testosterone).

In a rebuttal to our BMJ editorial, Stéphane Bermon, a director in the IAAF Health and Science Department, wrote that the IAAF regulation testosterone cut-off point of 5nmol/l is not arbitrary, but rather aims to include women with polycystic ovarian syndrome but to exclude women with differences of sex development. The glaring inconsistency here is that we simply cannot distinguish between these groups based on blood testosterone alone, never mind determining who is sensitive to testosterone and so has a supposed “performance advantage”.

The ‘sex testing’ of women athletes

Just because regulations exist does not mean that they are evidence based, ethical, or even effective. The crux here is that this kind of regulation has its legacy in the long and problematic history of “sex testing” women athletes. It is no accident that the vast majority of athletes affected by these regulations are black women and women of colour from the global south who do not conform to Western ideals of femininity.We don’t yet know what full evidence, beyond a review from Bermon and colleagues, before the current CAS panel is. But we do know that sex and gender are incredibly complex. Historically we have defined humans as binary “male” or “female”, based on what we knew then about genes and anatomy. This was a clear and useful way of categorising sports participation. But 21st-century medical and social sciences have since progressed, and we now know that both biological sex and sociocultural gender are much more complicated than that.

Read more: Why are Olympic athletes copping so much abuse? It all comes down to gender

In the animal kingdom, there are many species that are hermaphrodite, and in humans we now know there is a spectrum of sex (that includes people who are intersex) and gender (that includes people who are transgender). The complexity of sex in particular as a melange of genes, hormones, anatomy, biology can no longer be classified simply with a binary definition of male or female. It is, therefore, unfair and unethical for the IAAF to make new regulations for women’s sport – to the effect of excluding some women - based on outdated definitions and understandings.

It’s important to also understand the unintentional outcomes of regulations such as the one in question, including the ways in which regulations may potentially breach human rights. The Universal Declaration of Player Rights, which deals with the intersection of sport and human rights, reminds that an athlete’s right to participate in sport cannot be limited by gender (or any other identity-related factor, including sex). So we must understand both this history and unintentional outcomes of policy, including the ways in which regulations may entrench existing power relations.

Given that sport is currently organised according to the binary, and that this is unlikely to change in the near future, then men’s and women’s categories should be predicated on inclusivity. As Jennifer Doyle writes: “Women’s sports is not a defensive structure from which men are excluded so that women might flourish. It is, in fact, the opposite of this: it is, potentially, a radically inclusive space which has the capacity to destroy the public’s ideas about gender and gender difference precisely because gender is always in play in women’s sports in ways that it is not in men’s sports.”

The IAAF case matters because it is fundamentally about all women’s rights to participate in sport. If we do begin to regulate the participation of women with differences of sex development, then it will in effect stigmatise women athletes by categorising, labelling, and excluding them without scientific evidence or ethical consideration. Women should be allowed to compete with women, period. Otherwise we’re starting to talk about genetic superiority with no basis in truth, or humanity.

Sheree Bekker, Prize Research Fellow, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labels:

discrimination,

human rights,

Politics,

science,

women

Thursday, December 5, 2019

Olympia

Another version

Modern use of Olympia:

Some famous parts of Olympia

Monday, October 7, 2019

Prime Minister Abe at Rio Olympics, and Vladimir Putin in hockey exhibition

Labels:

Ice hockey,

Japan,

Modern Olympics,

Politics,

Russia

Saturday, October 5, 2019

Book review of the day: The Ideals of Global Sport: From Peace to Human Rights

John Soares. Review of Keys, Barbara J., ed., The Ideals of Global Sport: From Peace to Human Rights.

H-Diplo, H-Net Reviews.

October, 2019.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=54282

Quote from the review's conclusion:

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=54282

Quote from the review's conclusion:

In their conclusion, Keys and Burke argue that “as commercialism, doping, corruption, and gigantism spread an ever larger pall over sport mega-events, the need for a countervailing set of moral claims that can justify and excuse the excesses grows in tandem” (p. 223). Significantly, they point out, “the paucity of evidence” that these moral “claims are grounded in fact have almost never acted as a brake on the impetus to make such claims.” They write, convincingly, that “our craving for meaning and moral value guarantees that we will continue to invest our most grandiose events with a capacity to do good that they have yet to earn.” And yet, despite many disappointments, that moral veneer “has also, fitfully and sometimes unwittingly, helped reduce some of those wrongs” (p. 224). This clear and judicious conclusion is a fitting cap to a collection of essays that so commendably describes and explains the fraught connections between “mega” sport, moral improvement, and human rights. It deserves a wide readership among historians of international relations, sport, and the impact of nongovernmental agencies.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)